The Car as Pandemic Media Space

Based on two personal observations or anecdotes, this article engages with the car as a site of confession and the driving mirror as a screen of both control and evasion. It argues that that pandemic media space is a space of displacement where established dichotomies perish: the amateur and the professional, the private and the public, the here and there, as well as the past and the present.

Maybe it says something about cinema that its history has so often been told in parallels. There are the parallel tracks of cinema and the railway (Kirby 1997), the parallel and intertwining trajectories of cinema and psychoanalysis (Bergstrom 1999), and the parallel histories and experiences of cinema and the automobile. The cinema and the car are both inventions of a significant period of technological innovation, the period of the 1870s through the 1910s, which, among other things, brought the world dynamite, the telephone, the gramophone, electricity, airplanes, and industrial chemistry (Smil 2005). Cars have been featured in films since the earliest days of cinema, often as vehicles of a joint experience of viewing/seeing and driving, and sometimes of being driven over, as in Cecil Hepworth’s 1900 short film How It Feels to Be Run Over. As Jeffrey Ruoff argues, cinema itself can be understood as “an audiovisual vehicle,” which opens up the “filmic fourth dimension,” an emblem of the multifaceted constellations of transportation and media devices in the twentieth century (Ruoff 2006, 1ff.). Particularly in the first half of the twentieth century cinema, an image of movement and an image in movement, aligned with the automobile in western imperialist scenarios of global mobility, as for instance in the documentary films sponsored by French automobile manufacturers in the 1920s “that served as potent symbols of the French automobile industry and France geopolitical [colonial] ambitions” on the African Continent during the interwar period (Bloom 2006, 139). On a more granular level, the automobile became closely intertwined with the emerging practice of bourgeois amateur filmmaking from the 1920s onwards, with the automobile serving as a privileged subject, preferred mode of transportation, and occasional substitute tripod for those who could afford not just an automobile, but a small-gauge camera, too.

Today’s media and transportation ecologies are even more interdependent, and their specific constellations have multiplied and become more diverse.[1] Travel is highly mediatized[2] while digital screens as such have become mobile and ubiquitous; cars are now devices for mobility and mobile computer systems generating data about mobility in order to both facilitate and control movement.

In the following I will argue that that pandemic media space is a space of displacement where established dichotomies perish: the amateur and the professional, the private and the public, the here and there as well as the past and the present. My contribution uses two personal observations about the car as a pandemic media space in order to engage with the idea of the pandemic media space as a space of displacement: the car as a site of confession and the driving mirror as a screen of both control and evasion.

# the car as a site of confession

[Fig. 1] A Car Confession (Source: Natalie Bookchin: Laid Off, 2009)

As Natalie Bookchin’s thought-provoking video installation Laid Off (USA 2009) shows, YouTube has become a confessional platform on which to share a crisis. Bookchin’s video installation consists of a montage of video confessions of people who share their shock after losing a job. One important pattern Bookchin manages to reveal in her careful choreography is that quite a few of these videos are shot in private cars, presumably in a parking lot, more or less immediately after the firing. The inside of the car, recorded with a camera more or less in the position of a rear-view mirror, figures as a generic space of shared intimacy, a space that is both private and public, and in which we can talk to ourselves and simultaneously to others, our friends as well as an anonymous public who might potentially share our concerns.

The car confessional is now firmly established as a template of contemporary visual cultural and social and political articulation. It is perhaps no coincidence that the car confessional also produced one of the first viral videos of the COVID-19 crisis, the passionate rant of a mother of four from Israel who complains about the absurdities of homeschooling, a challenge and a sentiment many parents went through and could relate to.[3] Her car confessional went viral because of its topical subject matter and its raw, unfiltered appeal. However, as the woman’s YouTube channel indicates, this was not her first car confessional: she had already tried out this specific setting and role as a potential genre for herself before, but the pandemic helped her find her voice, so to speak. She failed to establish herself as a YouTube star, however; her subsequent videos reached a considerably smaller audience than the homeschooling video rant. What made that rant so poignant was that it highlighted the car’s double role as a safe space during the pandemic, thus adding new layers of meaning to the car confessional: a private space away from the living quarters of the family, a room of her own on four wheels, but also a safe space protected from the risk of infection, as I will argue in the following section.

# the rear-mirror as a screen

[Fig. 2] Rear mirror as screen (Source: Alexandra Schneider, 2020)

The night after the lockdown I decided to go on a car ride. Strangely enough it felt like “freedom” and “being safe” by riding a car “for fun.” Feelings, I have to admit, I had never before associated with riding in a car but had projected onto others: libertarian individualists, climate change deniers, heteronormative patres familias, and posers. But that is how I felt: safe from potential contagion by this new virus, absolved from having to practice physical distancing and free to move around the city wherever I wanted. Usually I would prefer to commute and travel by public transportation. But the pandemic made the privilege of being able to choose became apparent.

But then it was also something else about this car ride that was rather new to me. Shortly before the pandemic the old car which I usually drove had been replaced with a brand new car with a wide range of data-based driving support technologies. As I quickly learned, this was not a mere car but an audiovisual media device on wheels. The car obviously has the usual displays and screens to provide information about speed, directions, the state of the engine, etc. According to one’s preferred media genealogy, these screens serve to “filter” or to “project,” to display (to “show,” to “exhibit”) or monitor (to “observe,” to “check” or “control”). However, as a film and media scholar I was especially struck by realizing that this car features almost a dozen small cameras, which are not detectable by merely looking at the car and which turn this new, but not particularly fancy car into a kind of mobile CCTV device. The “parking assistance,” which is now more or less standard in new cars, of course relies on cameras, but this particular car also detects and decodes road signs, translating these readings into information for the driver—such as indications of the current speed limits—but also into decisions that the car’s electronic system makes regardless of the driver and often against the driver, such as adjustments to the car’s trajectory, deceleration, etc. One gadget especially struck me: a nearly invisible flash light which serves to illuminate road signs at night, a machine vision device which turns the car into a “seeing thing” that “looks” with its headlights, raising echoes of the anthropomorphic vehicles of Pixar’s CARS universe.

Finally, this car has one feature that particularly resonated with me after a semester of remote teaching and endless videoconferencing: the rear-view mirror that is connected to a camera at the back of the car, so that the mirror image can be replaced with a live transmission from that camera showing the road behind the car as if in a cinemascope framing. It was indeed Christian Metz who pointed out, in his last book L’ enonciation impersonelle ou le site du film (1991), that the windshield of a car often materializes as a kind of second screen in films.

This new kind of mirror-screen-device serves to maintain a clear view of the back of the car for the driver when the loading area is fully packed, with luggage or other items blocking the view to the rear. If the camera in the car confessional serves as a kind of rear-view mirror that is also a recording device and instantly creates a sense of proximity and intimacy, this rear-view mirror projection has a rather uncanny effect because it erases the presence of the other people in the car (who, in the case of Marion’s flight from Phoenix in Hitchock’s Vertigo haunt her as voices of absent bodies on the rear windshield). If the car confessional can be said to be modelled on the kind of conversation the driver could be having with his passengers in the back seat even while she is looking at them in the rear view mirror, the screen-mirror fed by the rear-view camera eliminates the passengers from the driver’s immediate visibility. They persist as accousmetric voices even as the viewer has a splendid widescreen view of the area behind the car. This visibility gap created by the machine vision devices of the car is, perhaps, an apt reminder of the fact that the purported safe space of the car can never be quite safe and always retains something uncanny about it. As much as we may communicate with the outside world through various looking devices, we are never quite at home in it. The car as pandemic media space is always a space of displacement.

# the screen as a monitoring device

![[Fig. 3] The screen as monitor (Source: Alexandra Schneider, 2020)](https://pandemicmedia.meson.press/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/PM_SCHNEIDER_Fig3_web-300x180.jpg) [Fig. 3] The screen as monitor (Source: Alexandra Schneider, 2020)

[Fig. 3] The screen as monitor (Source: Alexandra Schneider, 2020)

But then, at home, the laptop screen echoes the fake-mirror-screen in the car: if the rear-view devices in the car are a mirror turned screen, the video conferencing screen serves as both a screen and a mirror. Like a driver restlessly controlling her own behavior and adjusting to a constantly changing environment, the videoconference tools make me monitor and adjust myself to my own self-perception and my perception of the other participants. While participating in a video conference from home, I may be at home, but I am not safe from the pandemic media space of constant displacement.

In a footnote in his second article on the apparatus (le dispositif) Jean-Louis Baudry proposes distinguishing between the apparatus as a specific disposition of the viewing situation and the basic cinematographic apparatus (or l’appareil de base in French), which for him “concerns the ensemble of the equipment and operations necessary to the production of a film and its projection […].” For Baudry, the “basic cinematographic apparatus involves the film stock, the camera, developing, montage considered in its technical aspects, etc., as well as the apparatus (dispositif) of projection” (Baudry 1986, 317).

In approaching the new configurations of viewing devices and operative subjectivities, from driving to videoconferencing, it may be useful to return to this distinction and analyze the configuration of car, camera, and platforms both in terms of the basic apparatus and the viewing disposition. It may help us understand how the difference between home and not-home can easily be overruled and erased by continuities of the viewing dispositions of two seemingly clearly distinct spaces. As pandemic media, they rephrase the connections between outside and inside, public and private, but also between the amateur and the professional.

#beyond the screen

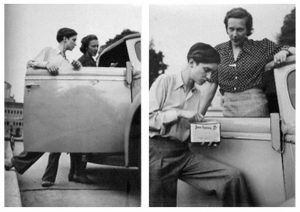

[Fig. 4] Beyond the screen (Source: Gilbert Meylon, 1939 / Fonds Ella Maillar, Musée de L’Elysée, Lausanne; 1939)

As soon as my screen fatigue goes away, I will revisit Ella Maillart’s and Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s books, photos, and films, in particular Nomades Afghans (Auf abenteuerlicher Fahrt durch Iran und Afghanistan, Ella Maillart, 1939/40), a film that resonates with both the professional and the amateur. Both Maillart and Schwarzenbach were pioneers of transgression, professional travelers who crossed lines and bent the norms and expectations of their time. They traveled through Central Asia by car, and with a camera. In light of our recent experiences, I expect to find in their work something that can help us unhinge the normalizing aspects of what is now consolidating into the pandemic media space of car and camera. A past that imagines the future.

References

Baudry, Jean-Louis 1986. “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in the Cinema,” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, edited by Philip Rosen. New York.

Bergstrom, Janet. 1999. Endless Night: Cinema and Psychoanalysis, Parallel Histories. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kirby, Lynne. 1997. Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema. Durham: Duke University Press.

Metz, Christian. 1991. L’ enunciation impersonelle ou le site du film. Paris: Meridiens Klicksieck.

Ruoff, Jeffrey. 2006. Virtual Voyages: Cinema and Travel. Durham: Duke University Press.

Smil, Vaclav. 2005. Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867–1914 and Their Lasting Impact, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Notes

[1] See also Lindsey B. Green-Simms: Postcolonial Automobility: Car Culture in West Africa. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

[2] See the contributions in the “Pacing the Airport” dossier of Social Text online, edited by Marie Sophie Beckmann, Rebecca Puchta, and Philipp Röding, June 2019. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/pacing-the-airport/