Divided, Together, Apart: How Split Screen Became Our Everyday Reality

The article looks at the history of the use of split screen in the cinema in order to provide a historical perspective to the proliferation of videoconferencing software during the COVID-19 pandemic. It argues that the specific configuration of the videoconference owes much to larger transformation of the media ecology—towards modularity, flexibility, relationality, and real-time feedback.

Zoom, Jitsi, Google Meet, WebEx, Skype, Microsoft Teams, BigBlueButton, FaceTime, DFNconf—the videoconferencing tools that we have learnt to use in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic are numerous, and their cluster-like appearance is often seen as proof of their novelty. But as film history and media archaeology has taught us incessantly, such ideas of innovation and newness have to be taken with a grain of salt. This is also the case when we think about the videoconference, which usually comes in the graphical configuration of the co-presence of talking heads in one larger frame. Film—and other (audio-)visual media—have a long history of imagining, depicting, negotiating, and presenting this dispositif, which has been given a lot of names: video call, image telephony, visual telegraph.[1] Casting a glance back at ways in which films have depicted this configuration, I am concerned in this essay with what we can learn from the cinema as an institution in which the social imaginary of this technology is presented.

Archaeology of the Divided and Mobile Screen

Images that show other images within a depicted space, frames that contain other frames are nothing new. Yet again, if we follow art historian Victor Stoichita we have a lead that helps us understand the situation we are facing (Stoichita 1997). Stoichita has argued that the tableau is a relatively recent invention that came about in the seventeenth century; before that, the image was bound to liturgical situations and to specific, fixed sites of exhibition such as churches. When the painting became autonomous and mobile, the image itself reacted with a discourse about this process which reflexively contributed to a cultural and social self-positioning. The image, so to speak, actively contributed to a theorization of its own function and ontology.

With moving images, we might be seeing a similar development at the moment. For the longest time, they were to be seen in specific spaces and circumstances like the cinema hall or they were connected to specific devices like the television set, which used to be a large and immobile piece of furniture.[2] With the mobilization of the computer, with the proliferation of hand-held devices such as the smart phone and the tablet, with the ubiquity of screens and terminals in public space, with the anticipation of holograms and data glasses, we live in a different environment characterized by images that behave very differently from the static arrangements that Stoichita was dealing with. The image has become autonomous and it has proliferated in ways that were unthinkable in the twentieth century.

Split Screen in the Cinema

The use of split screen in the cinema is more than a mere technical gimmick; it often shows how new technological developments have shaped our lives. Split screens in the cinema have typically been used to illustrate mediality—the transmission of signals over time and space. Consequently, the device has been employed to present media innovations that were new at the time. The telephone conversation, the live transmission of images on television, and later the decentralized direct transfer of data through digital networks were key domains for the use of split screen. The cinema—with its aesthetic means like mise-en-scène, editing, and sound design—reflects the world we inhabit, which is by now thoroughly saturated with media. The split screen has a specific graphical composition that predestines it for the display of mediality. It shows two (or more) spaces that are visibly distinct, yet presented in direct proximity within the image. It therefore mirrors the paradoxical configuration so typical of media: (spatial or temporal) distance is overcome through technological means, resulting in visual and/or aural closeness with the suppression of other sense perceptions.

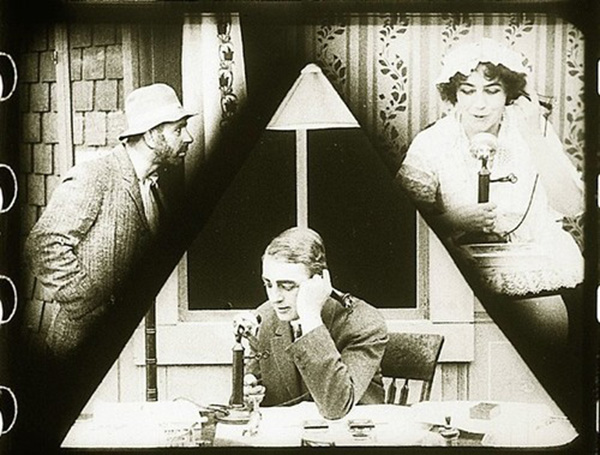

In the early years of the cinematograph, all of cinema was a special effect, so synthetic images like the split screen were much more common than they would later become. The assumption that a film image would show a seamless and navigable space in which human characters took physically possible actions was not yet the undisputed standard, as it would become in the classical paradigm. In early cinema, therefore, films would blend imaginary with real places and form complex arrangements of overlapping and morphing spaces. A good case to study the effects of normalization is Lois Weber’s film Suspense (US 1913), based on the same source material as D.W. Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (US 1910), a melodramatic story of a housewife and her toddler trapped in their house, while a burglar stalks the premises and the husband listens in via the telephone. Whereas Weber uses a split screen to present the situation (Fig. 1), Griffith opts for his signature parallel editing. Tom Gunning has shown how Griffith builds more tension through the simultaneously retarding and accelerating movement of parallel editing (Gunning 1991). While one might think that the presentation of simultaneous actions in one frame at the same time is more economical, it is in fact the concentration on specific aspect, as well as the acceleration possible through editing that proved to provide the model for decades to come. The split screen became an exception that was mainly used as an “invisible effect,” as in A Stolen Life (US 1948, Curtis Bernhardt) or The Parent Trap (US 1961, David Swift) in which the main actress plays a double role, masked by lines that are made invisible through décor and lighting.

Fig. 1: Suspense (US 1913, Lois Weber)

In the classical paradigm, the split screen went underground, only to reemerge at the tail end of classicism in comedies and thrillers. A number of films from the late 1950s onwards show a great innovative energy and a joy in trying out new techniques and technologies. At the same time, they invite the audience not just to mourn the situation or passively lean back, but they demonstrate ways to become creative with new media configurations. In the late classical period, there are films that suggest that the split screen is something temporary that needs to be overcome and left behind in favor of a shared physical and haptic space. The comedy Pillow Talk (US 1959, Michael Gordon) starts off with many scenes using the device, but as the film goes on—and the couple played by Doris Day and Rock Hudson increasingly occupies the same physical space—the split screen is used progressively less. The last 30 minutes of the film show the two protagonists constantly in the same room, making the technique superfluous. In fact, one scene shows an imaginary touch across the split screen in a kind of literalization of the dividing line between the two images—as the feet are in visual proximity, they appear to be touching each other and react accordingly (Figure 2), whereas in fact this haptic contact is but an epiphenomenon of the visual configuration.

This joke works on a double level: on the one hand, the graphical composition plays with the fact that we see the two spaces as adjacent on the screen, even though we know they cannot be so close that their feet could really touch. Our perceptual and epistemological registers process differently and they remain in tension. On the other hand, it evokes the knowledge of the spectator that censorship practices did not allow a tame Hollywood mainstream comedy to show the two (as of yet, unmarried) protagonists without clothes in the same bathtub (Hagener 2008). The mind can process this structural ambiguity between proximity and distance, between absence and presence that is the hallmark of mediality.

Figure 2: Pillow Talk (US 1959, Michael Gordon)

Modular Aesthetics

If the split screen discussed so far has been bound up with the fixed-site image (in the cinema, on the television set), development since the late twentieth century has put the moving image in motion. Whereas before it was either the spectators that moved (as tourists, passengers, attraction visitors) or the images that showed movement (see Friedberg 1993), now both have been put into motion. Following Stoichita we could claim that today’s multiplied frames within frames contribute to a discourse that reflects on the proliferation, miniaturization, mobilization, and modularization of visuality.

For roughly 20 to 30 years then, we have come to understand images as flexible. We are no longer an external observer of images that are watched from a distance as in Renaissance one-point perspective. What is typical of our situation is that the image is no longer absolutely fixed and stable in its aesthetic composition, in its use and context, or even in its manners of circulation. Images are stable neither in their form nor in their location; someone else might have produced an image, but still we can interact with it in real time, modify it and pass it along. Mike Figgis’s Timecode (US 1999) was one of the first films to address the simultaneity and complex layering of actions in real time. Today’s images are modular: we can use the text chat while in a videoconference, open additional windows and show them to others when we share our screen, we can enter text or transform sound into text. Children are now used to the fact that images are potentially scalable in every dimension (such as in Google Maps); the split screen presents a symbolic dimension of this modular and interactive nature of images as something we can act on and with.

The closest thing that the current aesthetics of videoconferencing resembles is indeed the quintessential post-9/11 TV series, 24 (US 2001-2010, Fox), in which Kiefer Sutherland plays the secret (or renegade) agent Jack Bauer who singlehandedly saves our civilization (or rather: the US of A) over and over again. Indeed, if we abstract from the reactionary politics of the series, the show turns into a family melodrama of paranoid dimensions in which literally everyone can betray anyone else. The hysterical storylines find their visual expression in complex split screen arrangements in which everything is connected with everything else—by media, by emotion, or by dependency (Figure 3). In fact, many of the acts of empathy and love, of hatred and betrayal cannot be disentangled from the media arrangements in which they happen. In this way, the extensions of man—to use a famous phrase from Marshall McLuhan—are body and language as much as databases and mobile phones, gestures and voices as much as networks and infrastructures. As much as we use these technologies, they also shape us and our lives.

Figure 3: 24 (US 2001-2010, Fox), season 3, episode 17

Our monitors and displays are mostly mobile and they are connected to cameras and other tracking devices, therefore what we see continually changes: things enter the frame and leave it again. Sometimes, the members of a videoconference walk through their flats and perform mundane tasks, we see other members of the household or we spot their pets. The off-screen space, the hors-champ, what normally stays outside and invisible enters the frame more frequently. At the same time some people seem to be meticulously planning how they stage their surroundings; the most frequent example during the COVID-19 pandemic was the use of background photographs in programs like Zoom, which many people used as acts of self-expression or ironic commentary. In this way, the videoconferences during the lockdowns and stay-at-home orders intensified a trend in social media: the private becomes increasingly public, but often in a staged and curtailed form. Videoconferences allow the constant controlling gaze at the self—if the hair is right, at what angle the chin looks best, what is visible in the background. This trend from social media of the careful visual management of the self is put into constant display through video calls.

Videoconferences are often rather audioconferences with an addition of images; we are asked to turn the video off, when the connection becomes unstable and we turn our microphones off, when we are not speaking—sounds are actually the central element of videoconferences and they are characterized by feedback effects and acoustic interferences. Do we hear a voice or just noise? Often, we cannot clearly identify sounds, an effect which can be puzzling or even uncanny. The cinema, by contrast, usually carefully orchestrates attention: image and sound work together, reinforce each other and collaborate in complex ways in order to make the image audible, the sound visible (Chion 2004). Coherent sound guides our attention, but in case of breakdown we revert to the chat, the image where we gesticulate or even write words on a slip of paper and present them to the camera.

One thing we can learn from the historical examples of split screen is how important sound is in understanding multiple images. In a three-dimensional room, we can locate the origin of a sound; in a two-dimensional image we need something visual to cue us to the source. Often, videoconference software includes tools that foreground the speaker by showing the video prominently or illuminating the frame—sometimes wrongly so, if one particular space is noisy. The conventionalized reaction is the muting of the microphones of the listeners. Speaking in a conversation becomes less a spontaneous reaction to something that has been said, than a carefully orchestrated intervention that needs to be planned and performed. The spontaneity of real interactions is turned into a scripted situation. To return once more to Timecode: the film in its initial release had a carefully orchestrated soundtrack which constantly cues the viewer to notice important narrative details that might otherwise go unnoticed. The DVD of the film allows the option to remix the four different soundtracks of the continuous 90-minute camera takes. And after the release of the film, Figgis toured international film festivals at which he would present “live remixes” of the soundtrack like a DJ.

If we survey the rich history of the split screen, we realize that we can—and should—deal creatively and productively with situations of novelty and constraint. There are countless possibilities in the affordances and limitations of videoconferences: from absurd theater and romantic comedies all the way to thrillers and horror films where participants of a call vanish one by one. A new form might be the desktop documentary, which found early incarnations in Noah (CA 2013, Walter Woodman/Patrick Cederberg) and Transformers Premake (US 2014, Kevin B. Lee). Film is part of a media ecosystem in which we can hardly distinguish in any clear way between cinema, television, streaming, and videoconferences. These forms continually mix and mingle, often merge and morph in unexpected ways.

Conclusion

Looking back at the longue durée of media history, the purported novelty of the videoconference gives way to a more nuanced and complicated picture. Many of the observations that are currently being made in relation to videoconferences—about the interaction between different frames, about the role of sound, about privacy and the performance of the self—can already be found in connection with the split screen. Beyond the concrete functionality of videoconferences, these images demonstrate how mediated visuality has transformed into a domain in which images are characterized by modularity, relationality, flexibility, and real-time interactivity. In this respect, the transformations of media from fixed and stable dispositifs to more flexible and open configurations find an exemplary case in the development from split screen to the videoconference. Not only in this respect, film history still offers a rich and dense history that can be mined in relation to our current media environments.

References

Chion, Michel. 2004. Audiovision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gunning, Tom. 1991. “Heard over the Phone: The Lonely Villa and the De Lorde Tradition of the Terrors of Technology.” Screen (32) 2 (summer 1991): 184–96.

Friedberg, Anne. 1993. Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hagener, Malte. 2008. “Geteilte Bilder, getrennte Betten: Zur Verwendung von Splitscreen in US-amerikanischen sex comedies, 1955–1965.” In Die Erotik des Blicks: Studien zur Filmästhetik und Unterhaltungskultur, edited by Werner Faulstich, Nadine Dablé, Malte Hagener, and Kathrin Rothemund, 25–37. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink.

McCarthy, Anna. 2001. Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space. Durham: Duke University Press.

Spigel, Lynn. 2001. TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stoichita, Victor. 1997. The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uricchio, William. 2004. “Storage, Simultaneity and the Media Technologies of Modernity.” In Allegories of Communication: Intermedial Concerns from Cinema to the Digital, edited by John Fullerton and Jan Olsson, 123–38. Rome: John Libbey.

Notes

[1] For this rich prehistory see Uricchio 2004.

[2] On the intersection of interior design and the television apparatus see McCarthy 2001 and Spigel 2008.